The easiest code I didn’t write

Automating rules (image generated with AI)

Automating rules (image generated with AI)

Implementation is getting cheaper. Thinking is not.

- A tiny mistake with a big blast radius

- Enter my one-hit song: unit tests 🕺🏽

- Letting AI sweat the small stuff

- But Mauri, isn’t this just busywork?

- Wiring it into CI

- AI changes the how, not the why

- The real skill shift

- Closing thoughts

A tiny mistake with a big blast radius

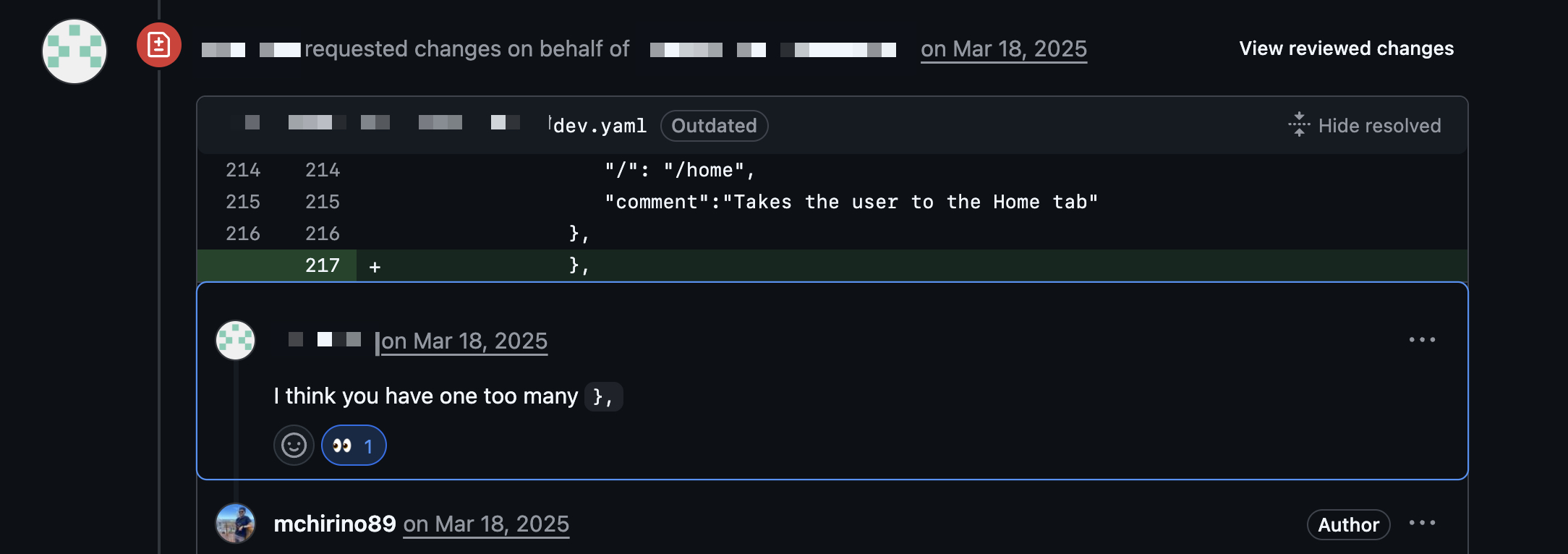

Awhile ago I did something utterly boring at work: I added a new universal link to one of our well‑known configuration files. We do this every once in a while. No fireworks. No architectural diagrams. Just a new entry in a place that has seen dozens of them before.

Except this time I messed it up.

The formatting was slightly off. Nothing dramatic at first glance. The kind of thing your brain happily autocorrects when you’ve been staring at YAML for too long. The scary part? By the time a teammate caught it, the change already had a couple of approvals (the minimum allowed by our internal policy to merge changes into the main branch).

Had this landed in production, it would have broken the entire .well-known endpoint crawled by Apple for universal links. That familiar feeling kicked in: where you replay alternate timelines in your head where it all went to 💩 and then you had some VERY awkard explaining to do.

I’ve written before about how fragile assumptions tend to hide in plain sight. This was one of those moments, just wearing a YAML costume.

Enter my one-hit song: unit tests 🕺🏽

This isn’t a story about blame or process failure. Code review worked. A human caught it. All good. But it did surface an uncomfortable question: What if the same mistake sneaks through next time?

The answer wasn’t “be more careful” (that never scales), but to remove this entire class of errors from the equation. So I did what any reasonable engineer would do: I added tests.

Not app tests. Not snapshot tests. Just a small, boring, very targeted set of unit tests validating the configuration itself. I’ve argued before that tests are about behavior, not implementation details. This was the same idea, applied outside of application code.

Letting AI sweat the small stuff

With Copilot’s help and a bit of creative thinking, I put together a small Python script that validates the formatting of the configmap entries where these well‑known paths live. The goal was intentionally boring:

- Parse the YAML

- Extract the values

- Assert that Apple expects a JSON object

- Assert that Android expects a JSON array

Nothing clever. No abstractions to blog about. Just encoded assumptions turned into executable rules.

import unittest

import yaml

import json

class TestConfig(unittest.TestCase):

def setUp(self):

self.files = [ # I've obfuscated the real routes for security reasons.

('dev', 'deployments/.../dev.yaml'),

('stage', 'deployments/.../stage.yaml'),

('prod', 'deployments/.../prod.yaml'),

('sandbox', 'deployments/.../sandbox.yaml'),

]

def test_well_known_android_json(self):

for name, file_path in self.files:

with self.subTest(file=name):

with open(file_path, 'r') as file:

config = yaml.safe_load(file)

data = config['configmap']['data']['well_known_android']

self.assertIsInstance(json.loads(data.strip()), list)

def test_well_known_apple_json(self):

for name, file_path in self.files:

with self.subTest(file=name):

with open(file_path, 'r') as file:

config = yaml.safe_load(file)

data = config['configmap']['data']['well_known_apple']

self.assertIsInstance(json.loads(data.strip()), dict)Did AI help write most of this? Absolutely.

Did AI decide what should be tested? Not even close.

But Mauri, isn’t this just busywork?

The thing is, this isn’t about the script. It’s about shifting responsibility from human memory to executable rules. Humans forget, YAML doesn’t care and JSON parsers are ruthless.

Once this test exists, a whole category of mistakes simply cannot reach production anymore. Not because people are smarter, but because the system is less forgiving. That’s leverage.

Wiring it into CI

A test that only runs on your machine is a suggestion. So I wired it into CI using a small GitHub Actions workflow:

name: Config validator

on:

pull_request:

branches:

- main

paths: # again, real path obfuscated

- 'deployments/../**' # <- One of my teammates suggested scoping this workflow only to changes in those files instead of running it everywhere.

jobs:

config_validator:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Fetch repo

uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Set up Python 3.9

uses: actions/setup-python@v5

with:

python-version: '3.9'

- name: Update package list

run: |

sudo apt update

- name: Set up dependencies

run: |

pip install --upgrade pip

pip install pyyaml

- name: Validate YAML configurations

run: python scripts/test_configmap.pyEven when AI helps write the code, humans still design the system.

AI changes the how, not the why

AI made the implementation details almost irrelevant. Writing Python, remembering APIs, parsing YAML — those are mechanical steps now.

What wasn’t automated:

- Identifying the risk

- Understanding the blast radius

- Deciding which invariants matter

- Choosing where in the pipeline to enforce them

That’s the work. It’s the same pattern I touched on in my previous post: tools change, mental models endure.

The real skill shift

If you squint, this story isn’t about Python, GitHub Actions, or configmaps. It’s about a shift in what it means to be effective as an engineer. Implementation used to be the bottleneck. Now it’s intent.

AI is excellent at answering “how do I write this?” but it’s still terrible at answering “should this exist?” and that’s fine. Because the creative act in software has never been about syntax. It’s about deciding where to draw lines, what to protect, and which assumptions deserve to be locked in with tests.

Closing thoughts

The real win wasn’t the script. It was turning a fragile assumption into a rule the system enforces for me. That’s the kind of help worth automating.