On Testing 3rd party frameworks without losing your hair 🤯

Image by Jan Vašek from Pixabay

Image by Jan Vašek from Pixabay

We’ve all been there: you’re on your typical developer day when suddenly a wild requirement appears! You proceed to wage the pros and cons of going for a in-house approach against using a battle tested framework by the community. Finally the later one wins and thus the development time for the feature gets shorter by a significant amount. However, how do we test something that’s out of our control? 🤔

Testing behavior, not functionality

Short answer is: we don’t, that’s why we went down the road of a community adopted framework. But make no mistake my friend, I’m not saying just because we selected a third-party framework that testing is out of the picture (far from it actually); what I meant is that given that the source code of it is black box for us, what we should aim to do is testing the interactions our project has with it produces in fact what we expect to. Let’s give it some more context so we don’t just keep this conversation in the imaginary abstract.

Let’s get a couple of things straight for starters

Disclaimer I: since third party dependencies integration to a swift project is not the main topic of this article, I’m assuming you know how to do it (there are many way to achieve this, many… many ways). Hence the starting point of this piece will be with Google maps already implemented in the project. There are plenty of posts out there explaining step by step the how and why of each, again: that’s not the main focus here.

Disclaimer II: some may look at this and complain I didn’t choose Apple’s native map support and therefore I’m getting myself into trouble to which I reply with a couple of arguments.

- The same principles I’ll expose here apply as well to first party framework: they’re all black box to use and we must test interaction/behavior rather than functionality. Apple themselves recommend to do so.

- I live and work for a Latin-American company that relies heavily on map’s accuracy to provide optimal UX and Apple haven’t payed too much attention to this side of the world with its MapKit support so there you have it: GoogleMaps for the win 🗺 🤺.

Our none cooperative requirement

Say you’re asked to show a map with some points of interest of yours (markers) in it and the marketing team wants to promote our app’s commercial effectiveness by showing to our partners how many tourists check their locations out -i.e.: number of clicks each one of them get-.

This looks pretty straight forward:

- Show a map.

- Load the partner’s customized markers .

- Track user’s tapping on each of them by leveraging proper delegation exposed by the framework.

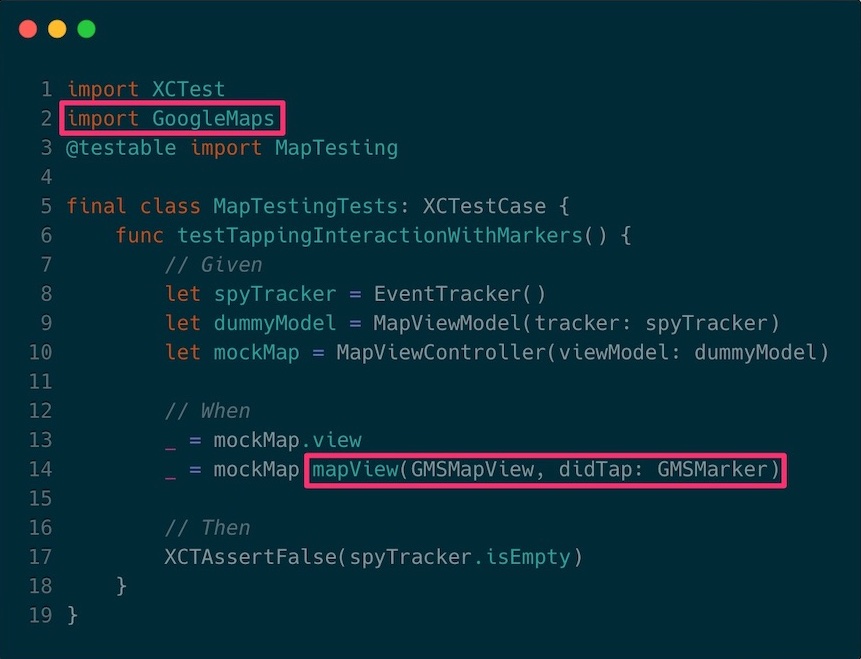

So far so good, “what’s the problem with this code Mauri?” you might be wondering… Let’s put a simple test in place to see what I mean:

We can use a spy here to assert proper tracking when the interaction occurs. However the first code smell is in line 14 where we’re forced to interact through Google map’s delegate directly (actually from line with the framework’s import statement). This implies either leaving our map view in the view controller publicly accessible or creating a dummy one in the spot in order to satisfy the caller requirement. Not only does this sound cumbersome at best (irresponsible and sloppy at worst) but by definition unit testing should happen in small isolated chunks of code without external dependencies (data base queries, network calls or in this case third party frameworks interactions). The very fact that we must add import GoogleMaps in our tests is a very strong red flag.

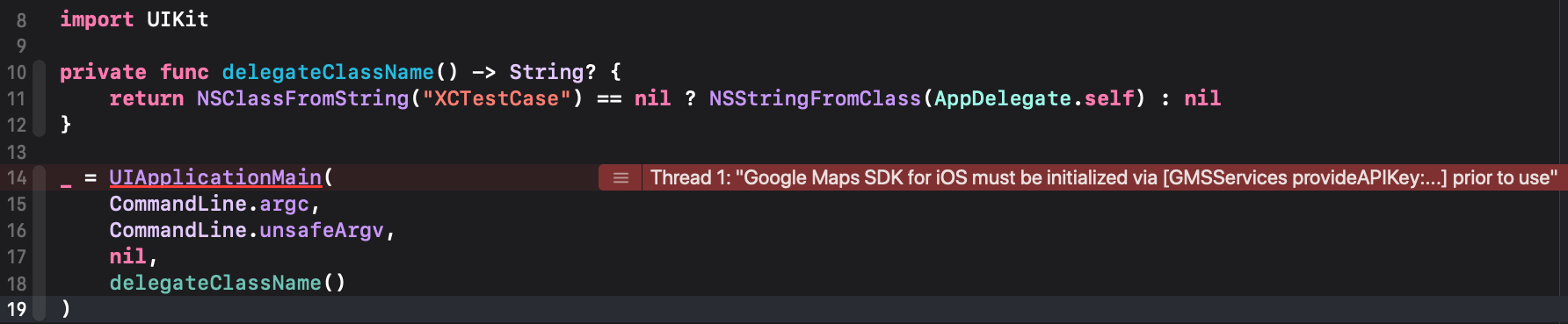

Furthermore, when we take this one step deeper and leave our tests at the very bare minimum by stripping the App’s main delegate from being called altogether we get this beautiful error:

It’s a no brainer to solve it but when you’re working on a decentralized architecture where each feature is its own separate module, you don’t have the luxury of your own AppDelegate and it becomes a roadblock. Again you might be thinking “you’ve painted yourself into a corner by choice there Mauri” but many literature has been written about breaking monoliths and why you (or your team) should generally aim in that direction.

Enough talk, show me the code!

What I’m about to share with you is an approach a fellow colleague of mine who has a lot more years than me in this taught me recently; what we need to do here is applying a facade that will interact on our behalf with the framework. A little bit of context from its wiki

Developers often use the facade design pattern when a system is very complex or difficult to understand because the system has many interdependent classes or because its source code is unavailable. This pattern hides the complexities of the larger system and provides a simpler interface to the client. It typically involves a single wrapper class that contains a set of members required by the client. These members access the system on behalf of the facade client and hide the implementation details.

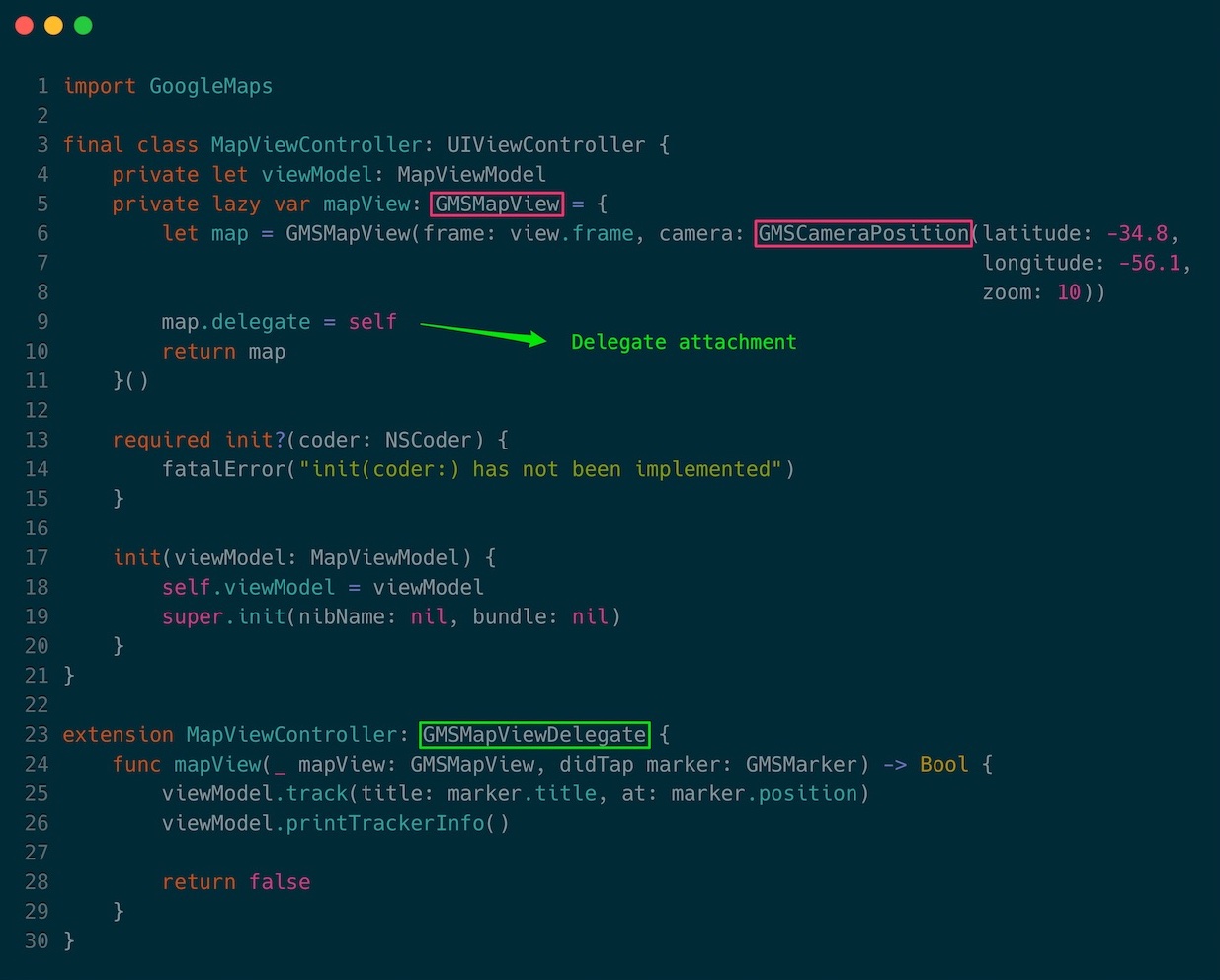

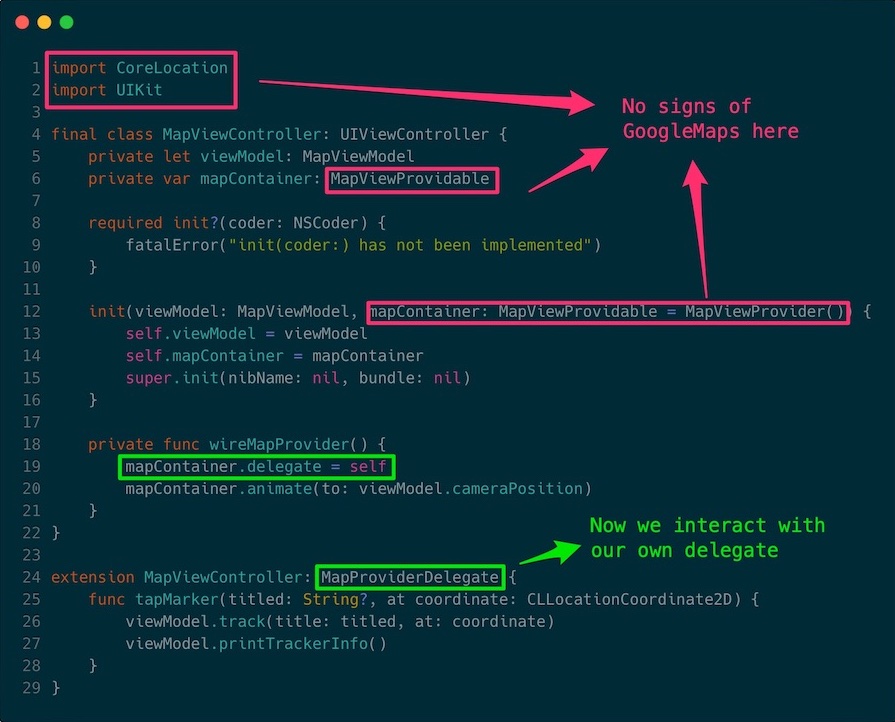

Let’s take a look at how our view controller looks right now:

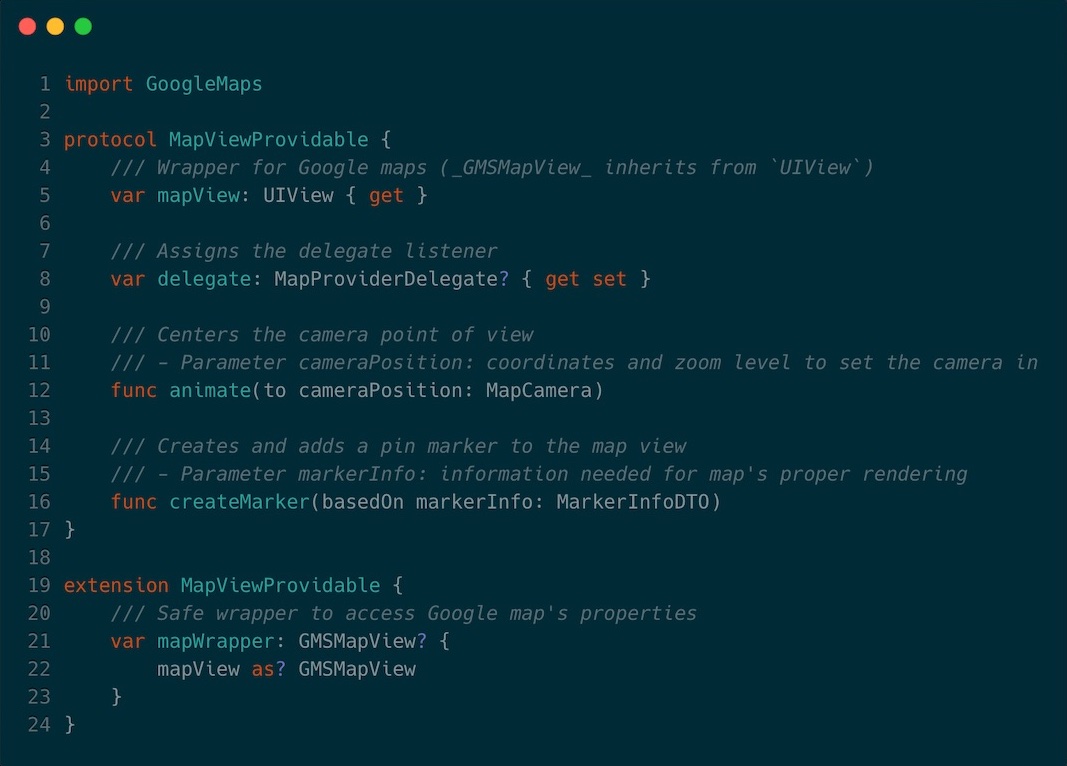

In red I marked the object to be replaced and in green there’s the delegate to interface with. Let’s proceed with the first one:

With this basic facade we accomplish plenty:

- Wrap the main map’s object behind a vanilla

UIView. - Set camera position by handing it our own custom

MapCameraobject. - Inject a

MapProviderDelegatewhich in turn will communicate between the framework and us, achieving dependency inversion this way. - Marker creation handling (this wasn’t view controller’s concern in the first place).

- Finally, there’s the

mapWrapperobject which type cast the instanced view asGMSMapViewone (we’ll see why a little bit further).

MapProviderDelegate is a class protocol with a single method (our current business need demands only this from him but this approach allows flexibility to grow it without breaking compilation). Let’s inject this into our view controller to check how it looks:

It’s worth noting that as a default parameter for the object MapViewProvidable is an instance of MapViewProvider

Wait, is this magic? How does it work?

I had a teacher back at the university who used to say

As engineers, you should know how things work so you don’t think Harry Potter lives in your machines

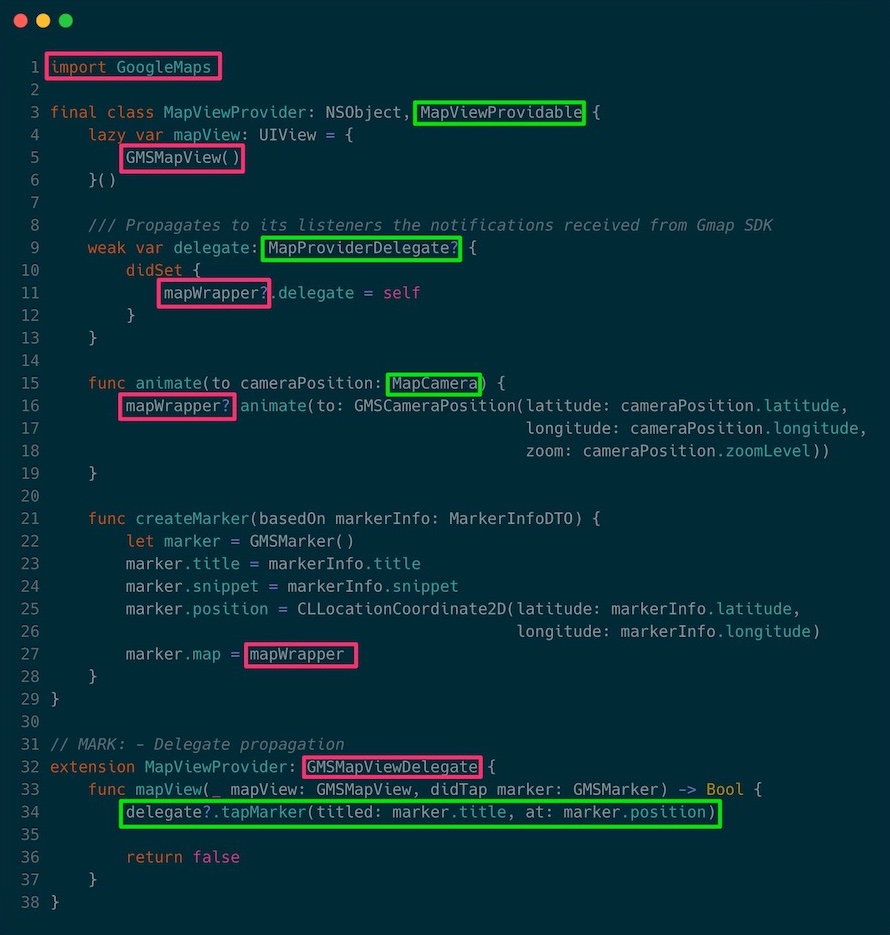

Let’s pick inside MapViewProvider

As we can see here’s where all communication with Google map’s framework and our delegate happens; in red are all external instances and in green our own objects (in fact, this is the only class that needs to import Google Maps). The secret sauce occurs between lines 9 and 13, as soon as the delegate’s MapProviderDelegate is set, mapWrapper is also set to the class itself thus propagating notifications whenever events from the framework are received (as seen in line 34 where only the information we care about is sent instead of an instance of GMSMapView as before)

What’s the point of adding this extra layer?

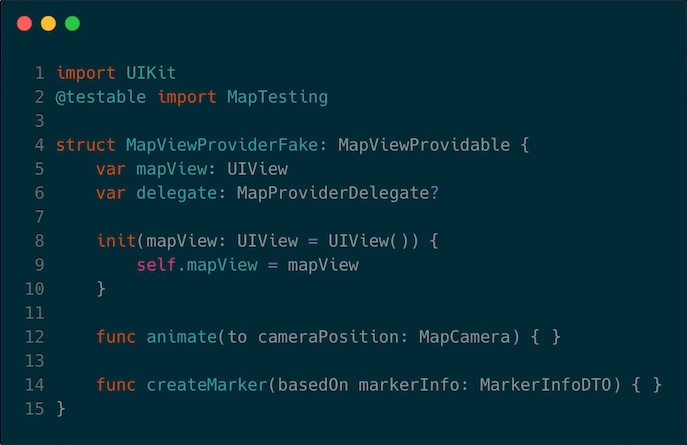

If you’re thinking the purpose of this extra layer is only aesthetics then think again, for starters I hate typing extra code just for the sake of coding. The power of this layer is that its type is an abstraction instead of a concrete implementation (inversion principle all over again) and thus it can be replaced on runtime by something else… That something can be very well a Fake object. From Martin Fowler’s blog:

Fake objects actually have working implementations, but usually take some shortcut which makes them not suitable for production

This is perfect for us. All we need is to create a Fake object that implements the MapViewProvidable protocol with just enough code to fulfill compiling requirements like so:

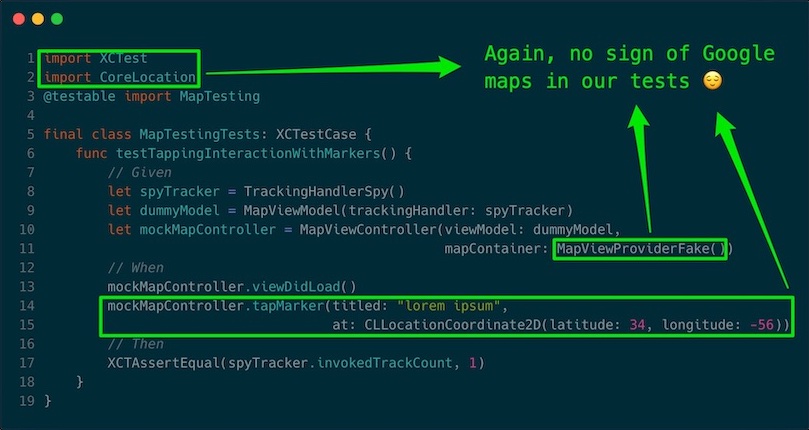

Now our unit tests verify interaction as they should

Conclusion

Dependency inversion and dependency injection might sound as scary terms but whenever someone toast them around in a conversation just know they refer to making properties in a system be interfaces instead of a concrete type (conform to protocols in Swift) and also be able to pass them from place to place, thus enabling us to replace them by a form of test double when automatic testing take place.

You can check the entire project here. I really hope this strategy serve you guys, I didn’t find too much information related to the specific topic back when I was battling against this which is what ultimately lead me to write this piece (a little contribution back to the community). Until next time 👋🏽

Tools used to make this writing a little bit faster and a little bit prettier:

- Swift Mock Generator: saves you lot of time of mindless mock and spy objects typing

- Nef: awesome tool for generating beautuful documentation

- Skitch: simple image editor to add annotations